Picking up this deep dive into Bowie’s inadvertent audio diary of 1970 after two years (!) away, it is finally time to examine the second disc. As mentioned, not many artists can claim to have a single year of artistic development so thoroughly documented in CD form as young Master Bowie did here, but thanks in large part to a new band member — Mick Ronson — alongside bassist and collaborator Tony Visconti, we get the rough with the smooth of that year as Bowie evolved through it.

This first disc showcased that growth, with an eclectic but intimate radio concert, sampling from across Bowie’s two-album career thus far (minus his hit single). In a way, it also illustrated the progression he was making from Newley-influenced story-songs from the first record to the better songwriting and more “hippie” influence of his time at the Beckinham Arts Lab.

The second disc of The Width of a Circle is more the “odds and ends” one. It features a set of tunes accompanying a Lindsey Kemp mime performance (one of them soon to be recycled), the singles from this period, including some alternate and/or stereo mixes are used — and in one case, the lead-up to the next album, and a (shorter this time) radio performance for DJ Andy Ferris, wrapping up with some 50th anniversary remixes by Tony Visconti.

The Andy Ferris show appearance, just six weeks after the one that makes up Disc 1, shows Ronson settling in nicely. It more strongly hints at Bowie’s latest change of direction under Mick’s guidance — including a telling cover song.

There’s a little overlap from the concert on Disc 1 to the March 1970 Ferris show, but the feel is quite different musically — and continues to help paint the picture of how Bowie got from his first two albums to his third LP, The Man Who Sold the World. Bowie and band were preparing to go into the studio the following month to record it, and the resulting album came out in the US in November of ’70 — capping off this extraordinarily transformative year.

Although the UK release had to wait until April of 1971, it was already clear by then that this new album was also to be a sales flop — but this time, the critical reviews were much better on both sides of the Atlantic. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves, and let’s instead check out this second disc of 1970’s activity, section by section.

Songs that turn on a mime

Disc 2 starts off four songs from “The Looking Glass Murders (or Pierrot in Turquoise),” which was a filmed version for Scottish Television of a mime show Kemp staged from late December of 1967 into the spring of the following year under the Pierrot in Turquoise title — the colour being suggested by Bowie, who was studying Buddhist lore at the time, where the colour is associated with the quality of “everlasting.”

In the original stage show, David sang three songs from his first album, accompanied on piano, and performed the role of “Cloud,” a kind of a minstrel narrator who helps bedevil Pierrot. In July of 1970, Kemp got in touch with Bowie to ask him to reprise his role and write some new songs for the now-reworked show, as it was being filmed.

The TV version starred Kemp as Pierrot, Annie Stainer as “Columbine” (Pierrot’s love interest), and Jack Birkitt as Harlequin (the threat to Pierrot’s romance), along with Bowie and pianist Michael Garrett. The new songs included “Threepenny Pierrot” — using the music of “London Bye Ta-Ta” — and two others, “Columbine” (which borrowed bits of “Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed”), and “The Mirror,” a fully original number.

The first song in the STV version was “When I Live My Dream,” a holdover from the first Bowie album. While the melody shows off an above-average musical skill, the lyrics are a really mixed bag — combining a schoolboy-like fantasy romance with some dark underpinnings of bitterness as the hero laments the loss (but hopeful return) of his “princess.” The reprise is just as wincing to listen to as the first time round.

In between is “Columbine,” written to establish the object of Pierrot’s desire and featuring equally theatrical lyrics, the more eloquent “Harlequin” (originally called “The Mirror”), and “Threepenny Pierrot,” performed in a music-hall style with simplistic lyrics. These songs should be considered a side-alley in Bowie’s career, as he was already starting to work on The Man Who Sold the World at the time, and had moved on in every artistic sense by this point.

The Singles of 1970

From here we move into the singles from this year, and the first is of course “The Prettiest Star,” one of Bowie’s rare flat-out love songs, created to flatter Angela ahead of their marriage. In all honesty, though, Biff Rose should have gotten a co-writing credit, as his influence is all over it (go listen to Rose’s “Angel Tension” if you disbelieve me).

That said, it features Bowie’s first recorded collaboration with Marc Bolan, who played electric guitar, Rick Wakeman on organ and celeste, and of course Bowie on acoustic and vocal. It got great reviews in the UK music press, but was ignored by the record-buying public in the UK, US, and everywhere else it was released.

The singles at this time came out in mono rather than stereo, because AM radio was so dominant. The version here is an alternative mix (still in mono) created back in the day by Visconti for US market promotion, but apparently (and audibly) wasn’t different enough, so it was forgotten about until now.

The “stereo” mix of the original version didn’t appear until The Best of David Bowie 1969-1974 album came along in 1997, and the artificial separation is very obvious. David re-did the song with a doo-wop/50s styling and Ronson rather than Bolan (but at least it was in stereo finally) for Aladdin Sane in ’73.

For my part, I’m delighted “The Prettiest Star” didn’t initially do that well. Yeah, it’s a lovely song — but if it had been another chart success like “Space Oddity,” he might have decided to work in the more conventional vein of love-song writing, because at this point he was still laser-focused on becoming a star. The fact that the song flopped so hard meant he had to find another way to become a rock god, and — thank heavens — he soon did.

“London Bye Ta-Ta” had been originally recorded as a potential single for Space Oddity back in ‘68, but was rejected (Deram dropped Bowie from the label after this). It was re-recorded in January of 1970 at the same time as “Prettiest Star” and with the same all-star guest cast, and was again supposed to have been a single, but got bumped by “The Prettiest Star,” which ended up having “Conversation Piece” as its b-side.

Consequently, this mono version of LBTT too was thrown into the vaults, and didn’t turn up again until Sound + Vision came out in 1989. The 2003 reissue of S+V included a previously-unreleased stereo mix of the song from 1970, which also turned up on the 2009 reissue of Space Oddity, and now appears here next to the mono version. There’s also a 2020 mix later on in the disc.

The final single from Space Oddity was a re-recorded electric version of “Memory of a Free Festival, Part 1” with the b-side being Part 2 of the same song, and they are both here in the 2015 remastered versions made for the Five Years Bowie box set. As the liner notes in the accompanying book for The Width of a Circle point out, this single not only featured Mick Ronson’s recording debut, but also the first use of a proper synthesizer on a Bowie record — no, the Stylophone on “Space Oddity” doesn’t count.

This electric version is also the first hint of Bowie’s stronger and more exuberant voice, hinting he will soon be leaving behind his more boyish and folkier tendencies that dominated the first two albums. This improved vocal style will serve him well on the harder Man Who Sold the World. This, though, is where he starts sounding like a real rock star.

Even though that single didn’t do well either, the new growth in David was spotted, and while Mercury had pretty much given up on Space Oddity at last, they seemed to be more impressed by his demo of a new song, “Holy Holy.” The first studio version of it was recorded by Bowie’s former bassist Herbie Flowers rather than Visconti, and released in January of ‘71 but went nowhere — as usual with Bowie singles up to this point.

The song was important, though, as the first indication that Bowie had taken on some influence from Bolan, and was starting to read a lot of Alastair Crowley, which greatly coloured The Man Who Sold the World and, eventually Ziggy Stardust. The first version heard on Width is the original version, produced and played on by Herbie Flowers (but remastered in 2015). You’ll immediately notice how oddly prominent Flowers’ bass is in his production of it …

We’ll be coming back to these records — plus “All the Madmen” — when we get to the all-new 2020 mixes of these singles by Visconti done for this project, and found at the end of this disc. All I’ll say for now is that technology — like Visconti — has come a long way in the interim.

The Sounds of the 70s: Andy Ferris

Short version: what a difference not-quite-three months makes. Recorded on March 25th of 1970, from the very opening notes it is clear that Mick Ronson has taken over all electric guitar duties, and the band (Tony on bass, John Cambridge on drums) have really gelled — freeing David to be a true R’n’R frontman, pushing his voice and only playing acoustic guitar as needed.

Going back to Disc 1’s live performance for John Peel, you’ll recall that it started with a lengthy solo performance from “troubadour” David before slowly bringing on Cambridge and Visconti for another two numbers, finally adding the just-met guitarist Ronson on for the second and more rocking half — slowing moving from acoustic, to soft-rock trio, and finally to a rock band.

This time, the very first notes we hear are those of Ronson, teasing out the intro to a muscular cover of Lou Reed’s “Waiting for the Man.” As Bowie struts his now completely fey-free vocals, Ronson plays over, under, and all around the band’s music bed like a kid at a new playground. Taking a short break for some noodling, the band pulls it all back together for a hell of a showy finish that only sounds odd because of the lack of 10,000 screaming fans cheering in the stadium that the band are all playing for in their minds.

The session was produced by a man named Bernie Andrews, who had previously helmed a couple of Radio One sessions for what was now (and only briefly) being called David Bowie’s Hype. The next number, “The Width of a Circle,” is one of the overlaps between this radio session and Peel’s live session from January, and the comparison is pretty jolting, even though the same lineup played on both.

To be fair, the previous version was when Ronson had just joined, still dominated by acoustic guitar, and Bowie’s definitely struggling a bit to sing over the band. For this Andy Ferris performance, the songs were recorded ahead of the show’s airing on April 6th, and treated like a studio recording, with overdubs and tracked vocals.

This time, Ronson leads the way, seconding himself on guitar. Bowie’s using copious echo, and this time has no trouble at all with his range and sustains. Following the first voice, we get multiple-overdubs of Bowie accompanying himself, for a better finish — though we’ll have to wait for the album version on the forthcoming Man Who Sold the World to hear the complete, eight-minute version, which was recorded just a few weeks after this.

Next up was a very restrained but definitely electric take on “The Wild-Eyed Boy from Freecloud,” where Ronson and the boys play it pretty safe and let Bowie take the lead. Ronson does take some time near the end to borrow a hook or two from Visconti’s symphonic album version of the song, which appeared on the Space Oddity album.

As the book notes, the song was one of Bowie’s favourites for a long time, and also appeared (in an acoustic version) as the b-side for that album’s title track, which of course became Bowie’s first hit. But the really interesting track here is what I think might be the world debut of “The Supermen,” which as it turns out was a brave thing to do.

Just two days earlier, the book tells us, the band attempted to record the song in studio, but weren’t happy with it. The version we hear on this performance is a re-do of that failed version, and although it is carried off successfully this time it does have some distinct differences to the slightly-rewritten version that made it onto MWStW.

Ronson’s guitar growls angrily on the rhythm track, allowing him to overdub the occasional leads, Bowie also doubles himself on the wailing “So softly, a supergod cries!” refrain, and the whole thing is Very Serious and Nietzchian. “The Supermen,” more than the other tracks in this performance, previews where Bowie’s head was at for the forthcoming third album.

The 2020 Mixes

For this box set and the 50th anniversary of The Man Who Sold the World, Parlophone went back to Tony Visconti in 2020 and asked him to create new mixes of the singles of 1970 detailed earlier, as well as “All the Madmen” which was almost … but then not … issued as a single in that year in advance of the forthcoming MWStW album. As it turns out, “Holy Holy” came out in its stead, but we’ll get to that.

Naturally, Visconti took full advantage of the masters as well as the latest in technology to create these new mixes. For this portion of the essay, I’ve opted to compare these new mixes to the original single version only. How do they compare?

Starting with “The Prettiest Star,” the immediately noticeable thing is the natural-sounding stereo, again drawn from the original mono recording. Listening to that original single, Bolan’s guitar is also more balanced and less pronounced, but still prominent.

Bowie’s vocal is right in the center as it should be, and echoed slightly in the run up to the title refrain. Everything sounds smoother, more polished, and in particular the synth, background vocal and strings get to move and sway around the channels, giving it the dreamlike effect that was clearly intended.

Ronson’s guitar, which replaces Bowie’s vocal for the break, also stays in the center — but unlike the original single, doesn’t play through to the end. Instead, Visconti gently fades Ronson’s last notes and extends the synth and strings combo to give the finale the same dreamlike quality they’ve had throughout the song — a really nice touch, in my opinion, and of course a huge improvement.

And speaking of huge improvements, the 1970 stereo mix of “London Bye Ta Ta” gets a massive makeover here, starting right with the opening. In the original, you opened with the acoustic in your left ear, followed by a blast of the rest of the band coming in a bar later on the right.

The 2020 mix offers a softer acoustic intro, followed by the band coming in more naturally on both channels. Bowie’s vocal is a little less pronounced, but smoother with just a slight reverb added, and broadly this version is much less “dynamic” and separated than the original single, but it’s also less “busy” — for example, the entire first verse and bridge loses the background singers, known as Sunny and Sue.

You can actually hear the piano work more clearly thanks to their omission on the bridge, but don’t worry — they show up fully on the second verse and bridge. Visconti has added strings, which feels added, but second time around they don’t diminish the BVs and other sounds.

There are some strings in the original, but only near the end, and for the 2020 version they’ve been balanced in nicely. Visconti adds a small bit of studio chat to the very end of the new version that wasn’t present on the single, but it’s contemporary from the original recording. On balance, I have to say I slightly prefer the original 1970 stereo single version, ham-fisted channel separation and all.

Now by contrast, Visconti’s 2020 mix of “Memory of a Free Festival” is a bloody masterpiece compared to the original single. The version of it presented here is the “single version,” running 5’23”, compared to the original single from 1970 which split the longer, 7.5-minute album version into two parts, with part 2 being the b-side.

As with the original, the lovely memory-song of the festival shifts gears halfway through, and becomes the “Sun Machine” jam mantra. But in this new version, every element is so sharp and gorgeous, with Bowie’s vocal so astonishingly clear. Every instrument, every note is so beautifully present and 100 percent mud-free, even with all the overdubbing of vocals in the second part.

On the original version, Bowie and the organ were mostly on the left, other elements mainly on the right until certain points, where both channels are used to full effect, and it was a very effective audio “special effect.” In the 2020 mix, Visconti creates a new version of the same trick: this time, everything is in full stereo, but the moments between the verses (and at other strategic points) are double-tracked and more separated at a higher level. It is a magical effect on headphones, maaaaan.

If you love this song like I do, this version feels like Bowie’s vision for it has finally been realised at long last, and it may even bring a tear to your eye. It makes the original single version sound like an 8-track tape that’s been left out in the rain.

Penultimately, we get to “All the Madmen,” which was intended as an advance promotional single (with the same song on the b-side) from the forthcoming MWStW album, but it never actually got released. The single (in mono) was supposed to be released on 4 November 1970 — the same date as the US album release — but visa problems meant that Bowie couldn’t “work” (perform) on a three-week tour of US radio stations, which didn’t help matters.

Some copies of this truncated version of “All the Madmen” were pressed, and a few still exist — they’re now rare collector’s items. The single edit runs just 3’15” compared to the album version’s more leisurely 5’43”, and really suffers for it.

It misses the eerie spoken word intro, for a start, and skips the first sub-chorus outright, leaving us with a sudden change in vocal mid-song to the “darker” styling more in line with his recent “rock star” singing ahead of the chorus. The intro starts off rather gently — with its intricate arrangement of acoustic guitar, gentle voice, and discant recorder duet (by Visconti and, surprisingly, Ronson).

Pay attention to that opening, because it’s important; it’s Hippie Bowie with a Perm leaving the building for good, even when David revisits his softer side on future albums. Just compare the sing-song ending of “Memory of a Free Festival” from Bowie’s second album with “Madmen’s” chant of “Zain, Zain, Zain, ouvre la chien.”

It’s just mind-boggling how different this same artist has become in under a year. More books, more sex, and maybe some drugs are about the only explanation for such a sea change that I can come up with.

As for the ending chant on “Madmen,” yes it’s willfully obtuse, but definitely sounds secret and potentially sinister. The first part of the chant on “Madmen” may refer to the Sword of Zain from the Qabalah, while the second part literally translates to “open the dog,” or more poetically, “release the hound.”

Bowie had been reading a lot of spiritual works around this time, including Thus Spake Zarathustra, which leads me to believe it’s a reference to Nietzshe’s idea of acknowledging and dealing with the dark side of one’s mind — which Bowie appears to now be embarking on.

This interpretation is reinforced by Bowie’s own experience with mental illness in his family, especially on his mother’s side. “All the Madmen” is, according to the man himself, about David’s brother Terry Burns — who spent most of his adult life in an insane asylum until his suicide in 1985.

According to a contemporaneous interview Bowie gave in ‘71, the song reflects Terry’s attitude that he preferred living in Cane Hill Hospital because the other patients there were “on his wavelength,” as he put it. The reason this unreleased single appears on Disc 2 is because it was created in 1970 and therefore should be included, and because Visconti has gone back and updated it here with a 50th anniversary mix.

The new version does a nice job of creating an excellent new stereo mix of the elements, starting with the open-string acoustic guitar (which seems like it’s been EQ’d for more bass). The second verse, with the recorders coming in and Woodmansey’s cymbal bell, are considerably clearer here than they were on the single, and the transition to electric with Ronson’s guitar and Visconti’s bass right on the phrase “such a long way down,” comes over much more smoothly in the new mix.

After the sub-chorus, Ronson bridges with dual harmonized guitar alongside Woody’s urgent drums, and the atmosphere change of the original is really “amped up” now. When we finally arrive at the chorus, Ron Mace’s strings-like Moog comes in to add the finishing touch, finally fusing with Ronson’s guitars exceptionally well.

Again, Visconti makes you feel like you’re listening to the master tape, rather than some nth-gen repressing. The handclaps, background vocals, and “secret message”-style refrain are truly present even as they slowly fade away, and overall it’s a big improvement to even the remastered version that appeared on the Five Years compilation.

Disc 2 ends with one last single in November of 1970, a non-album A-side of “Holy Holy,” backed with “Black Country Rock” from MWStW for the b-side, both in mono, again for the US market — since the new album was already out there, but wouldn’t be released in the UK until April of ‘71.

This is one of Bowie’s lowest-quality singles, given the repetition of the one-and-a-quarter verses he bothered to write (which are then repeated to fill the time, though less often as the album version), and the rather overwrought Nietzchian “Sex Magick” subject. That said, the chorus and Bowie’s vocal are pretty good, and the “Jaws” opening (predating that movie by a few years!) always brings me a smile.

But the big problem with the original single is the band Herbie Flowers put together for it (not Bowie’s band at all). They are just way too heavy-handed and, as is typical with Flower’s production, bass dominant. But that’s not to say there’s nothing interesting going on: there’s some vocal doubling with Bowie’s vocal, but it cuts out on the sub-chorus.

Naturally, Tony’s first job is to make this into stereo and clean things up, so naturally even just that makes it sound much better. Cheekily, he reprises the “Jaws” opener after the first verse, rather than the original’s guitar rise. Bowie’s doubled vocals are way clearer here, and are swapped for an all-new echo effect on the run-up to the chorus.

On the original, there is a single guitar “pluck” in between the line “I feel a devil in meeee” and the chorus, but in the new mix there’s a portion of a guitar slide that abruptly cuts off — not sure what Visconti was going for there. The first chorus downplays the original’s background vocals (but they are still there), and instead brings out a little bit of guitar noodling that had been buried in the original single.

The repeat of the half-verse just outright removes the (uncredited) background vocalist and instead doubles Bowie again, right through the chorus, throwing some echo on the guitars on the bridge before we go into a now-third repeat of the half-verse. Following that, Visconti moves Bowie singing “lie” a dozen times into an echoey background while more guitar fill, previously buried, is now clearly over the repetition.

As with the original single, the “lie, lie, lie (etc)” repetition simply alternates with the “to be a lie, high, high, high … oh my” to fill the remaining time till the fade out. One gets the feeling that this isn’t Tony’s favourite single then or now, and both the original and the new mix come over as very slight and full of filler … a sub-par production from a different producer then, and nothing Visconti really wants to reimagine now.

The “Digibook” and final thoughts

Despite the lacklustre final track on the second disc, The Width for a Circle as an overall project is both an excellent excavation of everything that was going on with Bowie and company in a particular year, an excellent “appetizer” before one dives into The Man Who Sold the World, and an attempt to document the transition from pop performer to (eventually, but not quite yet) rock god. Only in the pages of Nicholas Pegg’s outstanding “The Complete David Bowie” will you find more minutia and tracking of each and every appearance, song, and other public effort the man and his band put in to trying to make it big.

The book portion of the box set features a few rediscovered photos from the Haddon Hall sessions that produced the “Man Dress” cover of TMWStW for the UK version. In the US, Mercury’s cover was a nonsensical comic-book style cartoon with a cowboy holding a (holstered) rifle walking past what to Americans would look like some kind of mansion, but was in fact the insane asylum where Terry resided. Interestingly, the cowboy has a word ballon coming out of his mouth, but it’s blank … make of that what you will.

Famously, not only was the cover changed for the US market, the title of the album was changed for both the US and UK editions. Bowie wanted it called Metrobolist originally — some kind of play on the title of the 1927 film Metropolis — but Mercury changed it without consultation. In protest, Bowie hired photographer Keith Macmillan to do the “Man Dress” session for the later UK release.

In addition to mostly-unseen photos from that period, we also get pictures of the original handwritten lyrics to some of the songs, a bit of correspondence around the single releases, a couple of contemporaneous DB quotes from interviews about the songs, the various covers for the singles, and (best part) extensive liner notes and backstory for the radio shows and singles. Although the text is spare compared to the volume of music on the discs, it’s micro-focused on relevant details about the radio shows and singles, and very informative.

My one and only complaint about the book (called a “digi-book” because it’s part of the “digi-pack” packaging of the discs) is that that type is damn small and hard to read. As I said when summarising the first half of this package — if you love pre-Ziggy Bowie, then you might need this. Plus, it’s very highly-rated by buyers, and damn cheap, and you almost never see those two things together anymore.

I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74), recorded live in Detroit (with some bonus tracks from an even later Nashville date), showcases the band about six weeks later, and by this point the transformation of the show complete. More covers, more soulful arrangements, and yet more material intended for Young Americans (some of which didn’t actually make it onto the final album until later reissues). So from that perspective, this release — while just a straight soundboard boot with none of the mixing and post-production you’d get with an “official” release — is another interesting chapter of the rapid evolution in both the tour and Bowie himself over the course of some six months in this career-altering year.

I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74), recorded live in Detroit (with some bonus tracks from an even later Nashville date), showcases the band about six weeks later, and by this point the transformation of the show complete. More covers, more soulful arrangements, and yet more material intended for Young Americans (some of which didn’t actually make it onto the final album until later reissues). So from that perspective, this release — while just a straight soundboard boot with none of the mixing and post-production you’d get with an “official” release — is another interesting chapter of the rapid evolution in both the tour and Bowie himself over the course of some six months in this career-altering year. At this point in the tour, Bowie’s army of backing vocalists had been pruned back to six (down from seven). Their equal volume in the mix with the star of the show demonstrates, even more so than Cracked, a truly smooth unit that added a great deal of cover to the struggling frontman, and really keeps the slower songs exciting. It’s a treat to hear them at full force, even at the cost of other band members at times.

At this point in the tour, Bowie’s army of backing vocalists had been pruned back to six (down from seven). Their equal volume in the mix with the star of the show demonstrates, even more so than Cracked, a truly smooth unit that added a great deal of cover to the struggling frontman, and really keeps the slower songs exciting. It’s a treat to hear them at full force, even at the cost of other band members at times. A sharp stop and immediately we’re moved on to “John I’m Only Dancing (Again),” and the funk has officially been broken out. Even more so than on his first song, Bowie’s struggle to get his voice out is painfully obvious — so much so that he’s barely recognizable as the Bowie we’ve heard on the other live records. That said, he’s still willing to be even more playful with the lyrics. The overall energy, even here, is absolutely furious. Throughout the album, the crowd are very much in the background, but what you can hear of them indicates that they were thrilled to be there.

A sharp stop and immediately we’re moved on to “John I’m Only Dancing (Again),” and the funk has officially been broken out. Even more so than on his first song, Bowie’s struggle to get his voice out is painfully obvious — so much so that he’s barely recognizable as the Bowie we’ve heard on the other live records. That said, he’s still willing to be even more playful with the lyrics. The overall energy, even here, is absolutely furious. Throughout the album, the crowd are very much in the background, but what you can hear of them indicates that they were thrilled to be there.

The groove picks up some steam with the much superior “Somebody Up There Likes Me,” The band’s volume has slowly been creeping up in the mix throughout the course of disc two, and here everything is more or less in its proper balance. A brief “thank you!” at the end of the song, and we jerk over to a pretty joyous take on “Suffragette City,” with honky-took keyboards and the return of Earl Slick’s (mixed too low but rockin’) guitar, and the crowd goes appropriately wild at the end of it.

The groove picks up some steam with the much superior “Somebody Up There Likes Me,” The band’s volume has slowly been creeping up in the mix throughout the course of disc two, and here everything is more or less in its proper balance. A brief “thank you!” at the end of the song, and we jerk over to a pretty joyous take on “Suffragette City,” with honky-took keyboards and the return of Earl Slick’s (mixed too low but rockin’) guitar, and the crowd goes appropriately wild at the end of it. The encore starts off with a great treat, an Alomar-led take on “Panic In Detroit.” By this point and with this type of song, Bowie is starting to sound more Springsteen than British, but he’s clearly happy to carry on. For the first of the three “bonus tracks” from a later show in Nashville, Alomar is also front and center on Eddie Floyd & Steve Cropper’s “Knock on Wood,” which also makes good use of Sanborn and the bass-percussion combos that have been the gas in this engine all night long. If Bowie had recorded a version of the song similar to this arrangement, he might have pre-emptied Amii Stewart with a hit version of his own. The crowd clearly thought it was great.

The encore starts off with a great treat, an Alomar-led take on “Panic In Detroit.” By this point and with this type of song, Bowie is starting to sound more Springsteen than British, but he’s clearly happy to carry on. For the first of the three “bonus tracks” from a later show in Nashville, Alomar is also front and center on Eddie Floyd & Steve Cropper’s “Knock on Wood,” which also makes good use of Sanborn and the bass-percussion combos that have been the gas in this engine all night long. If Bowie had recorded a version of the song similar to this arrangement, he might have pre-emptied Amii Stewart with a hit version of his own. The crowd clearly thought it was great.

After having paid a fortune and put enormous effort into creating what amounted to a far-ahead-of-its-time touring rock show-cum-broadway musical, Bowie — now immersed in more funk, R&B, early disco, and other predominately African-American forms of music, an evolution from the black (and white) blues foundations of the early rock music from his youth — decided to scrap much of the existing set, props, and theatrics. Halfway through the tour, he reverted the show back to a relatively straightforward musical revue show. His management must have loved that.

After having paid a fortune and put enormous effort into creating what amounted to a far-ahead-of-its-time touring rock show-cum-broadway musical, Bowie — now immersed in more funk, R&B, early disco, and other predominately African-American forms of music, an evolution from the black (and white) blues foundations of the early rock music from his youth — decided to scrap much of the existing set, props, and theatrics. Halfway through the tour, he reverted the show back to a relatively straightforward musical revue show. His management must have loved that. Unmentioned last time was that while all of this was going on, the first — and in some senses most important — of documentaries on Bowie was being filmed by a young Alan Yentob, covering both the ongoing Diamond Dogs and Bowie’s own deteriorating mental and physical state, owing to his growing cocaine addition (accelerated, no doubt, by its easy availability in Los Angeles, where the tour was stationed for a seven-night run). The documentary was called “Cracked Actor” in part because of Bowie’s odd demeanour, and remains a vital look at him in the throes of addiction (as well as featuring rare footage of the actual Diamond Dogs tour set, and some of the performances).

Unmentioned last time was that while all of this was going on, the first — and in some senses most important — of documentaries on Bowie was being filmed by a young Alan Yentob, covering both the ongoing Diamond Dogs and Bowie’s own deteriorating mental and physical state, owing to his growing cocaine addition (accelerated, no doubt, by its easy availability in Los Angeles, where the tour was stationed for a seven-night run). The documentary was called “Cracked Actor” in part because of Bowie’s odd demeanour, and remains a vital look at him in the throes of addiction (as well as featuring rare footage of the actual Diamond Dogs tour set, and some of the performances). See our entry for David Live for details on the personnel changes and other details, but the revamped tour went back out on the road in September of 1974, and as mentioned a high-quality soundboard bootleg recording from the 5th of September (roughly the middle of the LA run) originally known as Strange Fascination, was released as a 2CD set in 1990. A different bootleg, known as Bowie 1974, is said to be from the same night — or at least one of the nights from that week-long run — but is claimed to be an audience recording rather than the soundboard.

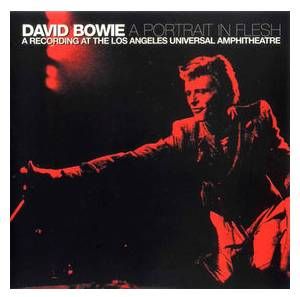

See our entry for David Live for details on the personnel changes and other details, but the revamped tour went back out on the road in September of 1974, and as mentioned a high-quality soundboard bootleg recording from the 5th of September (roughly the middle of the LA run) originally known as Strange Fascination, was released as a 2CD set in 1990. A different bootleg, known as Bowie 1974, is said to be from the same night — or at least one of the nights from that week-long run — but is claimed to be an audience recording rather than the soundboard. The original unedited recording was repressed under other titles, notably Glass Asylum and The Duke of LA. A later edit/remaster of the Strange Fascination source tape became the bootleg A Portrait in Flesh, released in 1998 (though with an original “copyright” of 1983, which remains unexplained). Besides the sound being remastered, Flesh differs from Strange Fascination in a few notable ways. The first was that Portrait trims down the overlong 10-minute (!!) intro of ambient cityscape and wild animal noises, as well as the “outro” of the original concert, which ended with the voice of the promoter on the PA advising that “David Bowie has left the building,” both of which can be heard on Strange.

The original unedited recording was repressed under other titles, notably Glass Asylum and The Duke of LA. A later edit/remaster of the Strange Fascination source tape became the bootleg A Portrait in Flesh, released in 1998 (though with an original “copyright” of 1983, which remains unexplained). Besides the sound being remastered, Flesh differs from Strange Fascination in a few notable ways. The first was that Portrait trims down the overlong 10-minute (!!) intro of ambient cityscape and wild animal noises, as well as the “outro” of the original concert, which ended with the voice of the promoter on the PA advising that “David Bowie has left the building,” both of which can be heard on Strange. Finally, this well-traveled soundboard tape made its way into the hands of Tony Visconti for an all-new mix job in 2016. Rebranded after both the song and the title of the documentary, the newly-official Cracked Actor album first appeared as a Record Store Day exclusive release in 2017 (following Bowie’s tragic death), and has since been released separately. Both the film and this album are highly recommended; the former documents Bowie in the worst excesses of his American influence (and cocaine), while the latter captures the hugely-revamped tour, featuring a band and singer-songwriter who were utterly on fire. To put it mildly, it paints quite a different picture than David Live. Together, the two live albums bear witness to Bowie’s latest evolution as an artist, struggling to paint his way out of a corner, and (just a couple of months later!) totally in thrall to his ingenius solution.

Finally, this well-traveled soundboard tape made its way into the hands of Tony Visconti for an all-new mix job in 2016. Rebranded after both the song and the title of the documentary, the newly-official Cracked Actor album first appeared as a Record Store Day exclusive release in 2017 (following Bowie’s tragic death), and has since been released separately. Both the film and this album are highly recommended; the former documents Bowie in the worst excesses of his American influence (and cocaine), while the latter captures the hugely-revamped tour, featuring a band and singer-songwriter who were utterly on fire. To put it mildly, it paints quite a different picture than David Live. Together, the two live albums bear witness to Bowie’s latest evolution as an artist, struggling to paint his way out of a corner, and (just a couple of months later!) totally in thrall to his ingenius solution.

Tony Visconti, called in to do a rush-mix of the live tapes he had not supervised, had to cope with a number of technical problems on the original performances, recorded over two nights in July in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania. The finished product in 1974 featured both harsh and variable qualities, with studio overdubs of both the horn work and background vocals being required to make it a saleable release. Visconti still says (of the original version) that it is the Bowie project he was involved in that he is least proud of.

Tony Visconti, called in to do a rush-mix of the live tapes he had not supervised, had to cope with a number of technical problems on the original performances, recorded over two nights in July in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania. The finished product in 1974 featured both harsh and variable qualities, with studio overdubs of both the horn work and background vocals being required to make it a saleable release. Visconti still says (of the original version) that it is the Bowie project he was involved in that he is least proud of.

This smartly moves into a rather chill opening for the first few lines of “Jean Genie” before bringing back the power for the chorus, then reverting back to the low-key intimacy for the second verse (where the audience can, remarkably, be heard clapping along). Throughout David Live, the audience reaction is mostly simply added at the end as (enthusiastic) punctuation on the musical sentence, and occasionally heard reacting to the beginning of a song.

This smartly moves into a rather chill opening for the first few lines of “Jean Genie” before bringing back the power for the chorus, then reverting back to the low-key intimacy for the second verse (where the audience can, remarkably, be heard clapping along). Throughout David Live, the audience reaction is mostly simply added at the end as (enthusiastic) punctuation on the musical sentence, and occasionally heard reacting to the beginning of a song.

Bowie also turned down a request to produce Queen’s second album, and refused an offer to collaborate on a film version of the comic book series *Octobriana,* (which would have starred another girlfriend, Amanda Lear). There exists (allegedly) a demo for another song called “Star” (not the same as the one on Ziggy), which was said to have been written for Lear. Wait, though, we’re not done! He also entertained and had a recorded chat with Nova Express author William S. Burroughs (which would come out a year later in Rolling Stone) in which he first revealed he was trying out Burroughs’ “cut-up” technique for writing — in David’s case for lyrics and a potential Ziggy Stardust musical that would have scenes that could be presented in random order. He continued using the technique, off and on, for the decades.

Bowie also turned down a request to produce Queen’s second album, and refused an offer to collaborate on a film version of the comic book series *Octobriana,* (which would have starred another girlfriend, Amanda Lear). There exists (allegedly) a demo for another song called “Star” (not the same as the one on Ziggy), which was said to have been written for Lear. Wait, though, we’re not done! He also entertained and had a recorded chat with Nova Express author William S. Burroughs (which would come out a year later in Rolling Stone) in which he first revealed he was trying out Burroughs’ “cut-up” technique for writing — in David’s case for lyrics and a potential Ziggy Stardust musical that would have scenes that could be presented in random order. He continued using the technique, off and on, for the decades. While an eventual staging was still on his mind (a number of drawn set ideas could be seen in the V&A “David Bowie Is” exhibit), the project ended up mostly flowing mostly into the first few minutes (and artwork) of Bowie’s studio album release for 1974, Diamond Dogs. Perhaps he would have created more material for the project (and the promising new persona of Halloween Jack) with more time, but Bowie was obligated to start touring again in the new year, so the record needed to get done and released. He salvaged what he could of the aborted 1984 material, threw in some Ziggy-type stuff to keep the kids happy, and stuffed it together into an extremely loose concept album (and this is one, barely) that definitely creates a mood, but falls more than a bit short on the narrative side.

While an eventual staging was still on his mind (a number of drawn set ideas could be seen in the V&A “David Bowie Is” exhibit), the project ended up mostly flowing mostly into the first few minutes (and artwork) of Bowie’s studio album release for 1974, Diamond Dogs. Perhaps he would have created more material for the project (and the promising new persona of Halloween Jack) with more time, but Bowie was obligated to start touring again in the new year, so the record needed to get done and released. He salvaged what he could of the aborted 1984 material, threw in some Ziggy-type stuff to keep the kids happy, and stuffed it together into an extremely loose concept album (and this is one, barely) that definitely creates a mood, but falls more than a bit short on the narrative side. Diamond Dogs opens with an introduction to set the mood and fill in just enough story to set imaginations working. “Future Legend,” a heady mashup of George Orwell, William Burroughs, and Anthony Burgess, would absolutely have been the curtain-rising start of the theatrical show, though calling it a “song” stretches credibility a bit.

Diamond Dogs opens with an introduction to set the mood and fill in just enough story to set imaginations working. “Future Legend,” a heady mashup of George Orwell, William Burroughs, and Anthony Burgess, would absolutely have been the curtain-rising start of the theatrical show, though calling it a “song” stretches credibility a bit. Bowie’s idea was that his burnt-out NYC gangs were kind of scavenger pimps-cum-Lord of the Flies in an anarchic ruin, left alone to do as they pleased — and what they pleased was to plunder the stores and bully the locals with a bit of ultraviolence. “When they pulled you out of the oxygen tent, you asked for the latest party” is another great opening line from David (and, years later, used visually for Screaming Lord Byron), and the song proceeds with considerable steam courtesy of all that ripping off of “It’s Only Rock and Roll.” Despite the strong opening gambit and catchy music, the song comes off the casual listener as just a considerably darker Stones number (and divorced of its context, that’s kinda what it is), and consequently as a single it didn’t do very well (by comparison with his recent successes), failing to crack the top 20 in the UK and not troubling the charts at all everywhere else.

Bowie’s idea was that his burnt-out NYC gangs were kind of scavenger pimps-cum-Lord of the Flies in an anarchic ruin, left alone to do as they pleased — and what they pleased was to plunder the stores and bully the locals with a bit of ultraviolence. “When they pulled you out of the oxygen tent, you asked for the latest party” is another great opening line from David (and, years later, used visually for Screaming Lord Byron), and the song proceeds with considerable steam courtesy of all that ripping off of “It’s Only Rock and Roll.” Despite the strong opening gambit and catchy music, the song comes off the casual listener as just a considerably darker Stones number (and divorced of its context, that’s kinda what it is), and consequently as a single it didn’t do very well (by comparison with his recent successes), failing to crack the top 20 in the UK and not troubling the charts at all everywhere else.

Recent Comments